Should you go to ITP?

A prospective ITP student recently reached out to me to ask about the program, providing a good opportunity to collect my thoughts about the last two years. Was it worth it? Is it a “good” program?

Of course, the answer is mostly, “it depends.”

1

ITP’s website says that

“ITP is a two-year graduate program located in the Tisch School of the Arts whose mission is to explore the imaginative use of communications technologies — how they might augment, improve, and bring delight and art into people’s lives. Perhaps the best way to describe us is as a Center for the Recently Possible.

Informally, ITP also describes itself as “engineering school for artists, and art school for engineers.” A brief look at the course list reveals titles like “New Interfaces for Musical Expression,” “Live Image Processing & Performance,” and “Tangible Interaction and Device Design.”

This description is a good introduction but belies one of ITP’s most unique and defining characteristics: its aggressive opposition to structure. For better or worse this philosophy impacts every aspect of the program and student experience.

2

Photo still taken from ITP promotional material.

At ITP students experiment with form and content in a whirlwind tour of possibility. Sneakers play music when you dance in them, wooden sculptures contort to mirror your image, and walls of 3D printed dicks rise and fall to track the stock market. At its best ITP is a chaotic, interdisciplinary melting pot where makers of all backgrounds inspire each other to develop creative, imaginative work.

It’s easy to see how imposing structure on the chaos could stifle the creativity and exploration that ITP prides itself on, and so the program curriculum notably lacks any hint of specialization or formalization. ITP scoffs at the idea of pre-requisites, subfield tracks, and consistent class offerings. Technology changes fast; if ITP is going to be the Center for the Recently Possible it needs nimbleness and flexibility, not deep investments into specific technologies or subprograms.

As much as they would hate to admit it, ITP has a lot in common with a certain kind of Silicon Valley hacker ethos.

Although this educational philosophy seems innovative or forward-thinking at first glance it actually has deep roots in ITP’s historical origins. But interactive and creative technology is incredibly different today than when ITP was founded in 1979. While it’s true one can find contemporary content like blockchain and XR among the course offerings, the “Center for the recently possible” has yet to adjust in form to the radically different technological landscape. In holding tight to its anti-structuralist ethos, ITP can’t fully acknowledge these shifts in technology nor in ITP’s position relative to the wider ecosystem of creative tech.

3

In 1979, the information age had not yet arrived. The first widely commercial personal computers were still a few years away and the Internet was still a US military research project. At the time ITP was an experimental film program, where “technology” referred more to the Sony Portapek (the first portable video camera) than to Arduino microcontrollers or machine learning algorithms.

The Commodore 64C, released in 1986

The Commodore 64C, released in 1986

But in 2021, fully utilizing technology encompasses more than just the ability to operate technical equipment. The ability to control and direct technical equipment - in a word, programming - has become an essential part of a technical creator’s toolkit1. The ability to move from what Ribbonfarm calls “below the API” to “above the API” in the context of artistic/creative practice is one of the most valuable things that ITP graduates leave with right now, both in an economic sense2 and a creative one.

However, ITP doesn’t seem to fully recognize this in its program structure, only providing one sort-of-required-but-not-really introductory coding class. This class is taught differently by each instructor and is graded pass/fail. As a result, students enter their second semester with only the barest minimum guarantee of coding ability. Moreover, the second semester (and beyond) is a true wild west, with no kinds of “staple” coding elective classes reliably offered in any given semester.3.

Red Burns, the godmother of ITP and the original proponent for the anti-structure educational philosophy of the program is famous for saying “the computer is just a tool.” She believed strongly in the strength of creativity over technical aptitude. She goes on, “It’s like a pen. You have to have a pen, and to know penmanship, but neither will write the book for you.”

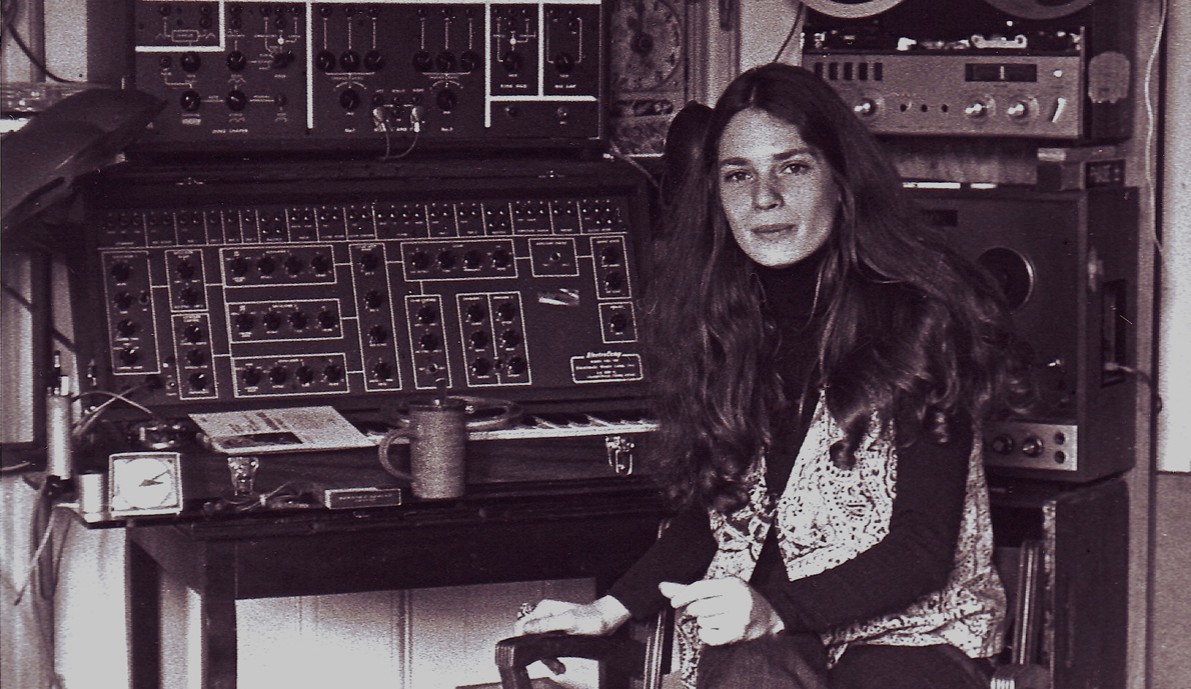

Red Burns, 1971. Image credit Cooper Hewitt Museum

Red Burns, 1971. Image credit Cooper Hewitt Museum

While I wholeheartedly agree with the general idea that creativity is as important (or even more important) than technical aptitude (If you don’t believe this you should just get a computer science degree!), ITPs specific attitude when it comes to computers is as outdated as Red’s pen metaphor.

You can learn how to use an audio recorder or film camera in a week. It takes years to become a competent programmer. The complexity of a computer encompasses a literal universe.

ITP doesn’t need to adopt an entire computer science curriculum. But its ignorance (or naivete) of the categorical difference between computers and other tools leads to noticeable degradations in the student experience.

One semester isn’t enough to cover everything you need to become an effective computer user. Every elective class that touches on software sets aside a significant portion of time to basic technical content that gets repeated across every class. Classes on topics as diverse as programmatic video manipulation, live sound synthesis, networked social interactions, generative poetry, embedded device machine learning duplicate literal hours of command line tutorials, Max/MSP introductions, and so forth. Do you want to take this class that uses X technology? Great, ITP will teach it to you! Did you like it, and want to go further? You’ll waste half the next semester learning the basics again, if a class on a similar topic is even offered.

In addition to the opportunity cost of wasted time experienced by probably half of the students during any given class, the wide variation in technical ability also degrades the creative aspects of the ITP experience. Conceptual critique and discussion suffers when half the projects for any given assignment are incomplete or artificially restricted in scope because of technical ability. Good penmanship is not sufficient, but it is necessary to write a book. How can students push the frontier of eg. data visualization forward when they don’t have a solid grasp on how to manipulate data programmatically?

4

This institutionally cavalier attitude isn’t exclusive to programming at ITP. It carries over to other fields as well. Since the 80s computer scientists, musicians, artists, writers, journalists, and so forth have gone and pioneered subfields like computer music, generative visual art, media studies, game design, data visualization, interactive fiction, etc. These fields have significantly matured as more and more people have gained access to computational tools, but you wouldn’t know it at ITP.

ITP basically completely ignores the existence and history of these subfields4, giving them only one semester’s worth at best and treating them as virgin territory still to be explored at worst. It doesn’t matter that music composition and performance has a thousands-of-years history - ITP students learn how to revolutionize music technology with a handful of lectures on the nature of pitch and rhythm. It doesn’t matter that computer music is over fifty years old with a rich set of compositional techniques built on each other over time - ITP can teach Markov chains (utilized in music in 1986, if not earlier) and call it a day.

Laurie Spiegel, creating computer music at Bell Labs in the 70s with probably the same or more interesting techniques than what’s taught at ITP

Laurie Spiegel, creating computer music at Bell Labs in the 70s with probably the same or more interesting techniques than what’s taught at ITP

ITP has no sequences of any kind. ITP doesn’t even reliably have a class touching on any given subfield during any given semester.5

This leads to a depressingly large portion of class and even thesis projects which simply retread the same ground over and over again. Students and faculty particularly interested in these subareas move on (reasonably so) to more specialized pastures6, leaving ITP feeling oddly behind the times. So much for “center for the recently possible.”

In my opinion the strongest subdepartment (if you could even call it that) at ITP is Physical Computing; is it a coincidence that Tom Igoe, a co-inventor of the Arduino microcontroller, and someone who is intimately familiar with the history of microcontrollers in creative contexts is involved?

5

ITP is a great place to be introduced to creating with technology. I think ITP is best for those with a somewhat lopsided experience between creating, and tech: traditional artists who have only dabbled in more advanced technology, or techies who have only dabbled in creative work.

I had lots of experience with technology coming in, and a moderate amount of experience with independent creating. I was often frustrated in looking to develop computer music and creative data practices at ITP. Instead, my favorite classes were all ones that involved simply making as many things as possible with support and critique provided by my classmates and with little to no institutional or academic content/support. I loved devoting a couple years of full time toward refining my own personal creative process and practice. I left ITP feeling fully empowered to pursue creative projects both professionally and personally, something that I certainly didn’t have before enrolling7.

6

ITP doesn’t need to completely pivot to teaching the state-of-the-art in computer science, music, data science, etc. with rigid prerequisites and classes all at once. The creative spirit at ITP is valuable, but I don’t think adding a little more structure would definitively kill it. There’s a lot of room for ITP to explore where exactly on the spectrum of structure it can sit.

Here are some of my ideas:

-

Commit to a handful “staple” courses that students can reliably expect to be taught year over year. ITP already does this with Introduction to Fabrication, which is a class usually offered every semester. Everyone loves it, and I believe its existence explains the overall high quality of sculpture and installation projects at ITP. This should be extended to other areas as well, like computer science, web development, music, generative graphics, game design, and so forth.

-

Offer skills based single credit or 2-credit courses during January or summer term to get rid of the horrendous duplication among electives. This could handle introductions to software/coding areas like Max/MSP, command line, Touchdesigner, Unity, Python, etc.

-

Allow faculty to suggest pre-requisites, or to devise their own one to two course sequences. How much more amazing would the New Instruments class be if it was suggested that students take Code of Music beforehand?

Notes

-

One could argue that programming is not strictly needed to “create with technology”; tools like the Adobe creative suite, CAD programs, Ableton Live and so forth certainly enable a great deal of creative possibility for their users. But I don’t think this argument can be taken seriously in good faith. Programming (or at least programmatic thinking) is a critical skill for any creative technology program in 2021. ITP students should be making Ableton in addition to using it. ↩

-

This matters, when the price tag of your so-called innovative, unconventional master’s program is of a typically regressive magnitude - try $100k on for size. ↩

-

When I attended (from 2019-2021) a web development class only ran one single time, and it wasn’t even a full 4 credit course. ↩

-

I want to emphasize that my complaints operate on the structural/institutional level. ITP has some fantastic faculty members engaging with their relevant academic/creative subfields. ↩

-

There’s something to be said for preferring to develop new fields rather than develop within them, but I still feel like you need to acknowledge the existence of the current state of the art before you can create something new. Otherwise you’re just going to make something someone already made at Bell labs in the 70s. ↩

-

Frank Lantz, the creator of the famous Universal Paperclips game was originally an ITP faculty member. He wanted to introduce a game design sequence to the curriculum and got stonewalled out, leading to the creation of the NYU Game Center. ↩

-

It seems scary, but I often wonder what it would have been like to quit my job and simply give myself permission to spend time creating, while seeking out community in other ways. ↩

Sign up for the mailing list

Comments